Dave DeBusschere was nicknamed “Big D,” where the “D” stood for Defense.

A hard-nosed, tenacious forward, DeBusschere was one of the game’s all-time best defenders. He was named to the All-Defensive First Team in each of the award’s first six years of existence. DeBusschere was average in size at 6-foot-6 and 225 pounds, but he possessed a work ethic that was second to none. During his 12-year NBA career he represented the epitome of the blue-collar basketball star.

From our partners:

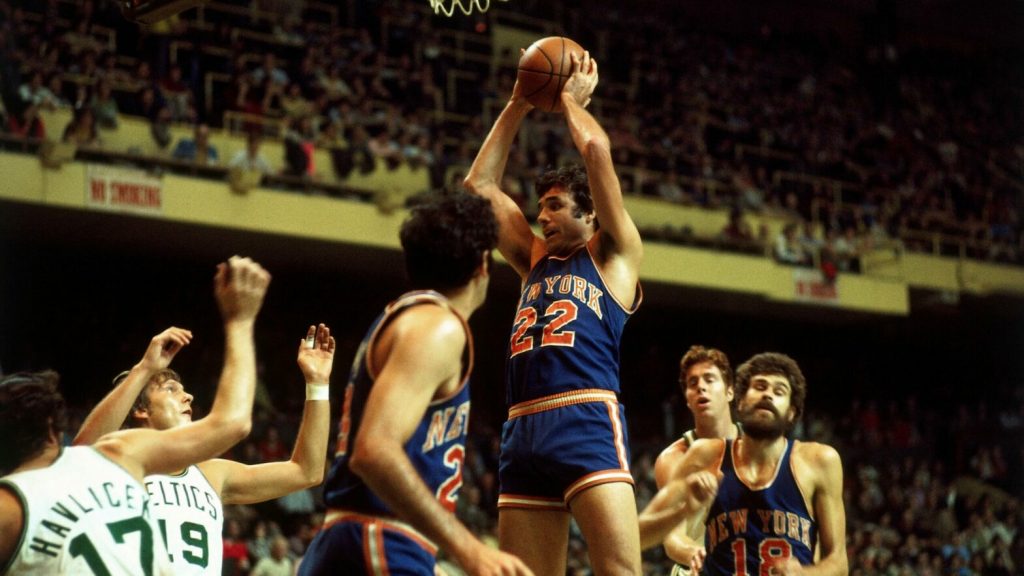

The dark-haired, rugged-looking DeBusschere roamed the hardwood with a determined grimace, a set jaw, and a jersey drenched with perspiration. Rival players knew they were in for a hard night’s work when they faced him. His style was a hallmark of the 1970s Knicks and he remains a part of New York lore even after his death at 62 years old in 2003 from a heart attack.

“There’s not one other guy in this league who gives the 100 percent DeBusschere does, every night, every game of the season, at both ends of the court,” Bill Bridges of the Atlanta Hawks once told Newsday.

The “D” could also stand for Detroit. DeBusschere was a folk hero in that city, where he grew up and starred at baseball as well as basketball. He attended Austin Catholic High School and led its basketball team to a state championship; was the star hurler on a baseball team that won the city championship and also pitched a local team to a national junior championship.

Colleges everywhere beckoned, but DeBusschere stayed home and attended the University of Detroit. He averaged 24.8 ppg as the school made one NCAA tournament and two NIT appearances. He also starred as a pitcher for the Titans’ baseball team, which played in three NCAA tournaments.

Upon graduation in 1962 DeBusschere was faced with a choice between baseball and basketball. In the early 1960s, basketball didn’t match the popularity of the diamond. Bucking tradition, DeBusschere decided to try his hand at both sports. He snagged a $75,000 signing bonus from the Chicago White Sox and received a $15,000 contract from the Detroit Pistons, who had claimed him as a territorial draft pick.

DeBusschere played professional baseball for four seasons. A tall right-handed pitcher with a lively fastball, he was called up by the White Sox in 1963 and went 3-4 with a 3.09 ERA. During the next two years, DeBusschere compiled a 25-9 record for Chicago’s Class AAA Indianapolis farm club.

Meanwhile, DeBusschere’s NBA career got off to an auspicious start. During the 1962-63 season, he averaged 12.7 ppg and was selected to the NBA All-Rookie Team. From the very beginning DeBusschere exhibited solid offensive skills. Although he battled for many of his points under the basket, he also proved that he could score with a good, if inconsistent, long-range shot. He handled the ball well for a big man, and occasionally the Pistons used him at guard. DeBusschere also displayed uncommon maturity for a rookie. He may have looked like a bruiser, but he was smart, analytical and cool-headed on the court.

The Pistons made the playoffs during DeBusschere’s rookie season, but in 1963-64, bad luck struck. DeBusschere broke his leg and played in only 15 games and Detroit managed only 23 wins. Although DeBusschere began the 1964-65 campaign healthy, the team limped through a poor start. In November, Pistons owner Fred Zollner made a dramatic move — he appointed DeBusschere player-coach. At age 24, DeBusschere became the youngest coach in NBA history.

It was speculated that DeBusschere had been given coaching duties to entice him away from baseball. If so, the plan worked. Although he played one more season of minor-league baseball, DeBusschere ended his dual-sport career shortly thereafter when he refused to accept a call-up from the White Sox at the end of 1965. He was reportedly unhappy that Chicago hadn’t kept him on the major league roster that spring. With basketball training camp beginning, his coaching duties were needed and he had to make a choice.

DeBusschere’s stint as coach was not successful. With the notable exception of himself, his Detroit teams were handicapped by a lack of talent. When coach DeBusschere asked the general managers of other teams which Pistons they would trade for, the answer was always the same: “You.”

Inexperience and youth probably limited his effectiveness — DeBusschere was barely 18 months out of college when he assumed coaching duties. He labored for almost three seasons at the helm before he was replaced by Donnis Butcher after the 1966-67 season. DeBusschere, who was 79-143 as a coach, retired from his post but remained with the Pistons as a player.

DeBusschere often said that he learned a great deal about basketball from his experience as a coach but that he found it burdensome. “It was a relief to give up coaching,” he later told Newsday. “I realize now there were things I wasn’t mature enough to handle. As soon as I was back on my own again, I had my best season. I was scoring better, rebounding better, defending better and doing everything else better.”

Over the years, DeBusschere’s talents were coveted by a number of teams, but the New York Knicks were more persistent than most. Every year the Knicks tried to pry him loose from Detroit but were continually rebuffed. “DeBusschere was our Holy Grail,” Knicks coach William “Red” Holzman later revealed in his book, A View from the Bench.

The situation changed, however, when Paul Seymour took over as the Pistons’ coach. Eager to revamp the club, he wanted new players, and DeBusschere was the team’s most marketable star. In December 1968, Detroit finally agreed to send him to the Knicks in return for center Walt Bellamy and guard Howard Komives.

For DeBusschere, escaping to New York was like being reborn. “As a coach I was very frustrated, losing all the time,” he said. “And as a player all I could look backward on was six years of losing. When they announced the trade, I was happy to be coming to a winner.”

The Knicks had high hopes that DeBusschere would prove solidify their frontcourt and shore up a run to the title. With Bellamy gone, Willis Reed was able to shift from forward to center. DeBusschere’s muscle and his rebounding prowess at the power forward position allowed the Knicks to play sharp-shooting Cazzie Russell and to use finesse player Bill Bradley at the other forward spot.

DeBusschere enjoyed immediate success in New York, finishing the 1968-69 season with 16.3 ppg and a berth on the All-NBA Second Team. He then helped the Knicks advance to the Eastern Division finals, which they lost to the Boston Celtics in six games.

Although he wasn’t a great shooter, DeBusschere had the potential to score 20 points every night. He tended to score in bursts, now and then rattling off a string of long jumpers from the corner. Like Bradley, he also excelled at sneaking behind picks to find an opening from where he could pop a 5-foot jumper. And he was masterful at sliding past his man to tap in an offensive rebound.

His chief role with the Knicks, however, was to collect key rebounds and shut down the opposing team’s best forward. A defensive catalyst, DeBusschere put his coaching experience to good use for New York, leading a smart, cagey Knicks unit that sacrificed individual achievements for team goals.

“I didn’t realize he was as good as he was until we got him,” Holzman said. “I always knew he was an outstanding player, but not this good. It’s often that way, I suppose. You don’t realize how good a guy is until you see him play every night.”

Former Hawks coach Richie Guerin shared Holzman’s high opinion of DeBusschere: “Dave is one of the 10 best forwards I have ever seen play basketball, and he just may be one of the five or six best I have ever seen.”

In 1969-70, the talent-laden Knicks found themselves in the national spotlight. The Knicks of that era had undeniable personality with Walt “Clyde” Frazier, a flashy guard with an even flashier wardrobe, leading the way. Rhodes Scholar “Dollar Bill” Bradley was a thinking man’s player, who would become a well-respected U.S Senator and presidential hopeful, but then was a great passer and shooter. And at the hub was gutsy 6-foot-9 Reed.

The physical DeBusschere was indeed the final piece in the Knicks’ championship puzzle. “Sometimes he’ll score only four or six points in 40 minutes,” Holzman told Newsday. “People say to me: ‘How come you play him so long?’ I say because he does a hell of a rebounding job for us, a hell of a job on defense for us.”

DeBusschere was an immediate hit with the fans, too. In contrast to Frazier and Bradley, DeBusschere was a “regular guy ” — a plain-spoken working stiff who enjoyed drinking beers in the locker room after games.

During that 1969-70 season, the Knicks lived up to their fans’ expectations. With chants of “DEE-fense” rocking Madison Square Garden, DeBusschere and his teammates roared through the league with a 60-22 record. During the playoffs they shut down the Baltimore Bullets in seven games, then blew past the Milwaukee Bucks and Lew Alcindor (later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) in five games to face the Los Angeles Lakers in The Finals.

The championship round was pure drama. It was the teamwork of the Knicks against the glamour of the Lakers, who were led by superstars Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West and Elgin Baylor. The final contest of the seven-game series is now legendary.

Reed, injured and expected to watch from the sidelines, electrified players and viewers alike when he took the court at Madison Square Garden at the start of the game. Limping up and down the floor, he nevertheless scored the Knicks’ first two baskets and inspired the team to a 113-99 victory.

For enquiries, product placements, sponsorships, and collaborations, connect with us at hello@zedista.com. We'd love to hear from you!

Our humans need coffee too! Your support is highly appreciated, thank you!